Electric vehicles (EVs) are becoming popular worldwide, and the boom is spreading to Southeast Asia. In Indonesia, the government is preparing charging infrastructure and tax incentives to encourage EV buyers and manufacturers. However, most EVs are still more expensive than their gas-guzzling counterparts, and charging stations remain sparse even in Jakarta.

Singaporean startup Oyika wants to tackle both problems. Working with electric motorcycle manufacturers, the company offers a weekly subscription plan that bundles a motorcycle with unlimited battery swaps. Since the company entered the Indonesian market in October 2020, it has attracted about 100 subscribers and established 16 battery swap stations in the Greater Jakarta area.

Larry Lim, President Director of PT Oyika Powered Solutions, Oyika’s Indonesian subsidiary, says the local market is perfect for electric motorcycles. “Indonesia has the largest number of motorcycles in Southeast Asia, and motorcycles are a part of life for the Indonesian people,” Lim told CompassList. “At the same time, motorcycles contribute to pollution problems, and Oyika wants to provide a solution to that.”

There are now 120m motorcycles in Indonesia, representing 85% of the total vehicle population in the country. Less than 0.1% of the motorcycles are electric.

Targeting ride-hailing and delivery drivers, Lim says Oyika already has a back-order of 30,000 subscription plans in Greater Jakartathat it hopes to fulfill by the end of 2022.

The parent company in Singapore has raised $4.4m from an investment round led by Singapore-based cleantech fund TRIREC and is raising $100m to expand its business across Southeast Asia. Lim said that “more than half" of the $100m Oyika plans to raise will be channeled to the Indonesian subsidiary.

Rent-to-own

Oyika offers a weekly subscription at IDR 265,000 for an electric motorcycle and access to battery swapping facilities in Indonesia. Lim said Oyika plans to develop this subscription plan into a rent-to-own scheme. If a subscriber continues to use the service for three years, Oyika will give the motorcycle to them. “It’s similar to telco subscription plans, where you get a smartphone bundled with the plan, and you get to keep it after two or three years,” Lim said.

The motorcycles are provided through partnerships with local brands such as Viar, Selis, Elvindo and Voltra, and foreign brands Niu and Super Soco. Oyika installs a custom discharge port on the motorcycles, allowing these different brands to use the same Oyika batteries. Two batteries are installed simultaneously, and Lim said most drivers travel 50–60 km with both batteries fully charged.

Motorcycles are a part of life for the Indonesian people

When the batteries are low on power, users can find the nearest swap stations using Oyika’s mobile app. These stations are built near supermarkets and other public areas, close to where most delivery riders are based. Oyika also provides 24/7 service to bring batteries to drivers who are too far from a swap station.

Oyika chose the battery swap route instead of plug-in charge stations because it would work better for drivers who are always on the go. “Long charging times are what causes people not to use EVs because it can take hours to fully recharge the batteries while pumping gasoline only takes a few minutes,” Lim said.

“This contributes to range anxiety and makes electric motorcycles less feasible for delivery drivers. By swapping batteries, the drivers can get back on the road quickly.”

Chicken-and-egg problem

Currently, Oyika only has around 100 subscribers, but the company plans to increase that number to 5,000 by the end of 2021 and 30,000 by the end of next year. Lim believes that Oyika will break even in Indonesia by the end of this year.

He added that the key to achieving Oyika’s targets is building “thousands” of battery swap stations. He describes it as a “chicken-and-egg” problem; without enough recharging or battery swap stations, riders will be discouraged from using EVs, but there is little incentive to build those stations without enough EVs.

Oyika’s approach is to build the infrastructure first while also making it easier to use and own EVs. “As we build more battery swapping stations, it will be convenient for users to swap batteries, and more people will come onboard to use electric motorcycles,” Lim said.

He added that the subscription and rent-to-own plan is meant to alleviate common concerns surrounding EVs. Besides range anxiety, Indonesians are worried about the reliability of the vehicles, availability of maintenance services, and the resale value of the vehicle.

“Money is always a big consideration, especially in terms of down payment and getting a loan,” Lim said. “People also think about how much they can resell a vehicle for after putting in so much money into the investment.

“The challenge is to make EVs more affordable to rent and own, and we are working to lower the barrier to entry.”

Beyond EVs

While Oyika’s priority in Indonesia is to fulfill their subscription backorder in Greater Jakarta, the company has already planned its expansion to other provinces and verticals. After strengthening its position in Greater Jakarta, Oyika plans to bring its battery swap scheme to Surabaya, East Java, which is Indonesia’s second-largest city in terms of population.

Besides building battery swap stations, Oyika plans to increase the number of electric motorcycles on the road by converting old combustion engine motorcycles into EVs. The plan is still in the early stages, but Lim said this would become a very affordable way for riders to start using EVs.

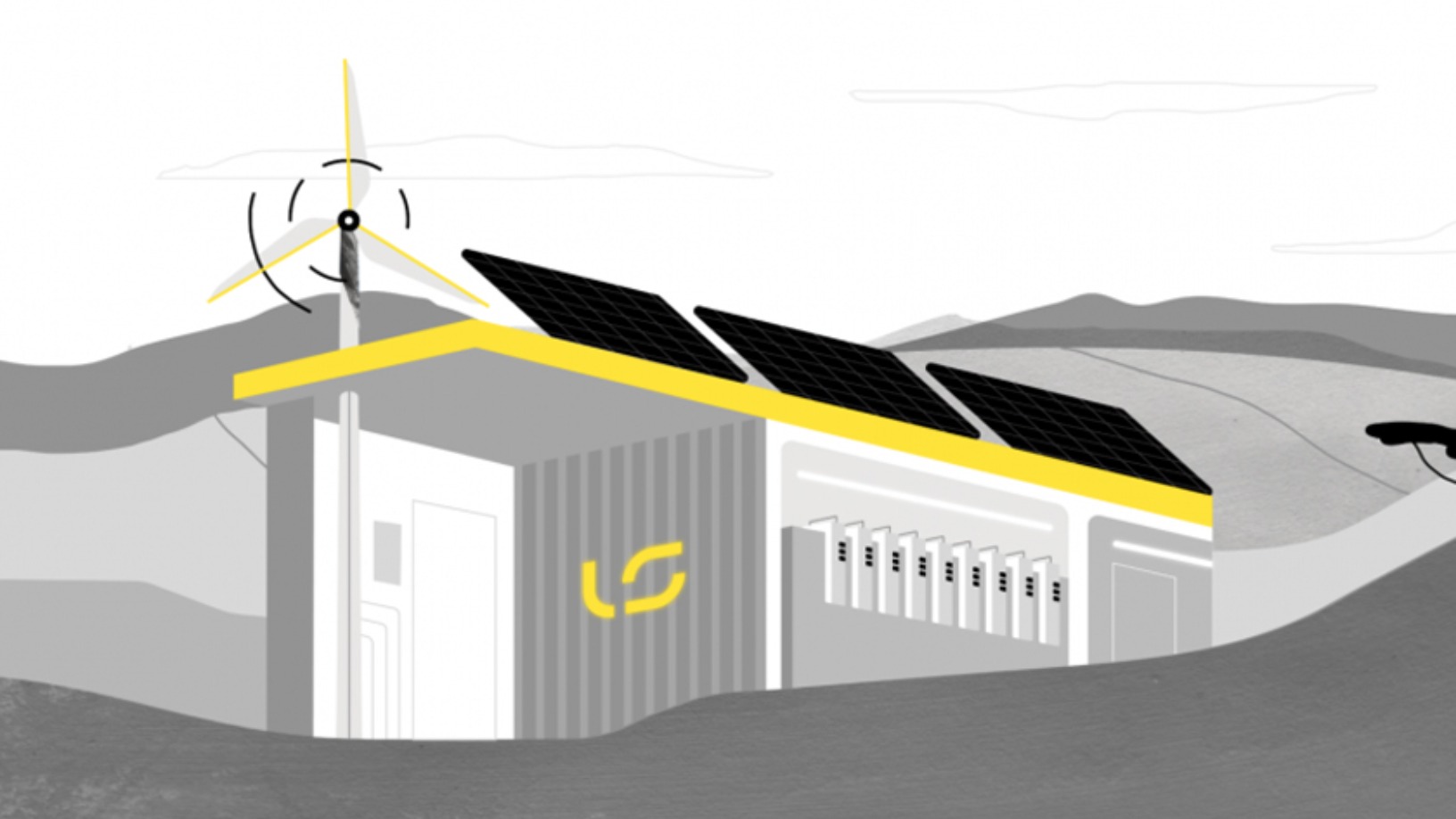

Oyika also has plans beyond EVs. Batteries that are no longer fit for EVs can store power from solar panels and provide electricity in disaster areas or off-grid rural regions. Oyika is developing a custom discharger for this purpose, which will use a similar battery-swap system to the company’s EV discharge ports.

Lim hopes that Oyika can complete the project on time to participate in a government tender to replace a similar system used in rural areas. “ About 97% of Indonesia is connected to the power grid, but there’s still the remaining 3% we need to take care of,” Lim said.