It was a germ of an idea two years ago when two female Hungarian scientists created a biosolution of plastic-eating bacteria that could be efficiently scaled for industrial use without producing any harmful effects. Seeking to take their research from lab to market, the pair co-founded and bootstrapped biotech startup Poliloop in 2019. A year on, they’re closing $2m worth of seed funding from Hungarian VC Vespucci.

Poliloop’s mission is to mitigate plastic pollution by offering an organic method of recycling the waste using harmless plastic-eating bacteria, with the byproduct going back into producing bioplastics. The funding will enable the startup to hire more industrial engineers so they could kickstart crucial tests for technology validation, industrial applications and commercial viability of scaling the bacteria cultures for waste management operations, Poliloop CEO and co-founder Liz Madaras told CompassList in an interview.

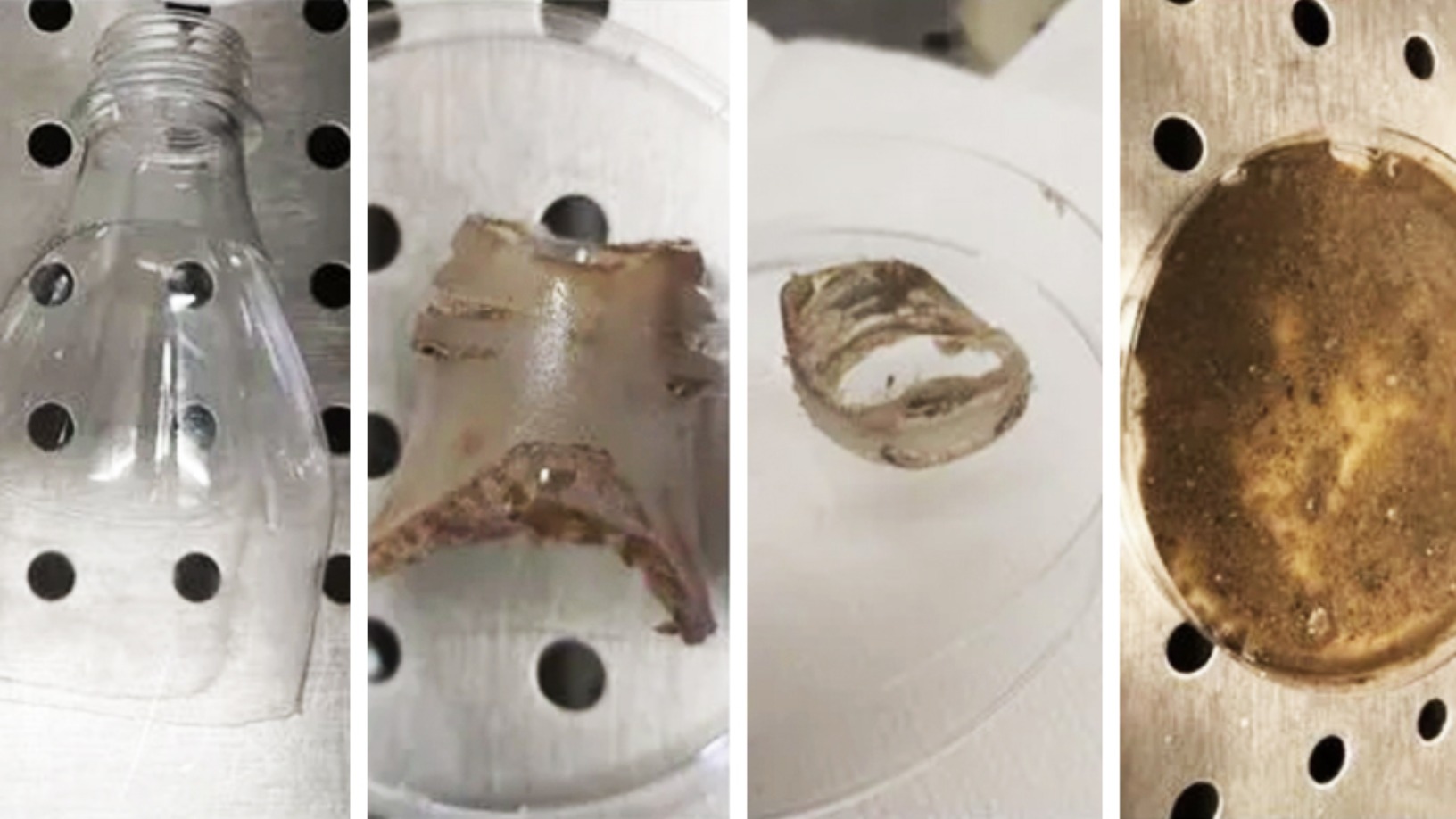

“We have worked very hard to grow the new bacteria in a special culture medium to enable them to actually eat the plastic,” she said via Skype. Although the bacteria cocktail is currently working at a slow pace, taking about two months to dissolve a single plastic film, the process doesn’t require any chemical pre-treatments.

“We tested the sludge and found that it’s nontoxic,” the bioengineer added. “This is because we mimic nature, we’re using the tools that had evolved over millions of years to get rid of something that humans have put into the environment.”

The pilot tests will also help to gauge if the lab-cultivated bacteria cocktail can be scaled for industrial use to clean up tons of city waste at low cost. The Budapest-based biotech startup joined the Techstars Hub accelerator earlier this year.

Existing solutions slow, costly

Only four years ago, a group of researchers discovered an organism capable of assimilating and degrading polymers while collecting samples from plastic-contaminated sediments near a Japanese bottle-recycling facility. The bacterium, named Ideonella Sakaiensis, was also featured in the March 2016 issue of a Science journal.

However, the Ideonella process involves complex treatments and takes nearly six weeks to biodegrade a single plastic film. With over 300m tons of plastic waste being disposed every year, the Ideonella solution was found to be nonviable for commercial recycling facilities.

Scientists worldwide have continued to look for new and more efficient polymer-dissolving bacteria. In India, researchers found ocean bacterial species that can degrade polyvinyl alcohol. A lake in Zurich also produced micro-organisms that can eat polyurethane. In 2018, scientists in the UK connected two Ideonella enzymes to speed up the plastic biodegradation. But not a single one was fast enough for commercial use and for integration into existing waste management systems.

“These solutions have been unprofitable and aren't operational at an industrial scale right now. So, I believe we might be able to offer a better solution,” Madaras said during her pitch for Poliloop under the Energy & Sustainability category at the South Summit virtual conference in October. A Coca Cola plastic bottle treated with Poliloop’s solution took less than 50 days to break down into organic sludge, she showed.

"As a manufacturer, we want to make the circular economy work in the long run by producing biodegradable plastics,” she added.

2022 commercial launch

Poliloop will start to pilot its biotechnology at a semi-industrial scale at the beginning of next year. The commercial launch is planned for 2022 after legal compliance issues have been taken care of.

“This is a completely new solution and we have to work out its capabilities and potential applications,” said Madaras, who co-founded Poliloop with chemical engineer Krisztina Lévay as CTO and transportation engineer Gábor Antal as COO.

Their core technology relies on the in-house production of the specially cultivated bacteria that can eat all sorts of single-use plastics like PET, PP, LDPE, HDPE, PS, CPE and EVA. Testing for industrial applications will start with a pilot project in Hungary.

“We aim to be a technological company rather than an infrastructure one; it’s the only way we can scale fast enough,” said Madaras.

At the core of Poliloop’s business model is licensing its biotechnology to waste management companies and municipalities. Another revenue source will come from consultancy services for waste management optimization based on the client’s existing waste streams.

“Our solution has to be applied on a very large scale to actually make a dent in the plastic crisis that we're facing,” she said. “Most likely the industrial deployment will be tailored to our customer's needs since the waste flow may differ by city, by region, and/or by company.”

Eyes Europe, North America markets

Madaras, who is a postgraduate student Budapest University of Technology and Economics, stressed the importance of creating synergies and collaboration among plastic waste producers and companies dealing with waste collection, recycling and disposal.

“We want to make sure this technology is accessible to other parts of the world,” she said. “By licensing our technology, we can help others to process their waste locally, where the waste is being produced.”

Future plans include international expansion, starting with Europe as the first target market followed by North America where legislation is more mature and flexible regarding waste management and circular economy models.

“We're not necessarily focusing on the local market, we're focusing on markets that have the right legislation in place for implementing our technology," she added. “We want to use our knowledge and background to build something that’s actually good for the world and can tackle one of the great issues that we're facing right now as global citizens.”