The shrimp industry is one of the few in Indonesia that managed positive growth during the Covid-19 pandemic. As of November 2020, shrimp exports from Indonesia reached a value of $1.86bn, up from $1.7bn over the whole of 2019. The Ministry for Maritime and Fishery has even set an ambitious target of $4.25bn revenue from shrimp exports by 2024.

For Liris Maduningtyas, the CEO of shrimp farming technology startup JALA, this presents an opportunity for her company to grow. In an interview with CompassList, she said JALA will launch a management franchise program for small- and medium-scale shrimp farms in May or June this year.

Under the planned franchise program, JALA will provide its IoT and data analytics tools to help shrimp farms improve their ponds’ water conditions. Maduningtyas said that fintech-based lenders will provide working capital support for the franchise businesses, but she declined to share which companies are working with her startup until the program is officially launched.

Despite the challenges brought by the Covid-19 pandemic, JALA grew in 2020, with the company’s SaaS platform and mobile app reaching 8,600 registered users monitoring more than 16,000 ponds. Maduningtyas also said that JALA is in the process of raising funds in a pre-Series A round. She declined to share the target time or amount, as discussions are still ongoing.

Franchises to help small farms

Maduningtyas said that guidance programs for shrimp farmers have existed for a long time, but they don’t provide farmers with the infrastructure or capital access they need to meaningfully increase their productivity. “We don’t just provide the operating expense, but we also assess the infrastructure [for upgrades],” Maduningtyas said.

“Small-scale farms produce seven tons [of shrimp] per hectare of ponds, while medium-to-large farms produce up to 13 tons per hectare,” Maduningtyas said. “These small, semi-intensive farms are our targets. We want to increase their productivity by 25-50%.”

JALA has also launched new products to support its franchise program. One of these is a microbubble diffuser that can oxygenate shrimp ponds, helping farmers control water quality. “With good oxygen levels, the survival rate and feed conversion ratio improves. Farmers need less feed to increase the mass of the shrimp,” Maduningtyas said.

“The Ministry of Maritime and Fishery wants to increase shrimp exports by 250% by 2024. That translates to at least a 20% increase in productivity per 3–4 month cycle. It’s a major challenge for shrimp farmers and we want to support them with our technology.”

More than just data

JALA started out in 2015 developing sensors for water quality in shrimp ponds, but was not initially successful. After joining accelerator programs held by aquaculture specialists Brinc and Hatch, it pivoted towards data analytics for shrimp farms, which is provided through a SaaS model.

“We learned that people did not want just raw data," Maduningtyas told CompassList in 2019. "They wanted to know what the data meant and what to do with it."

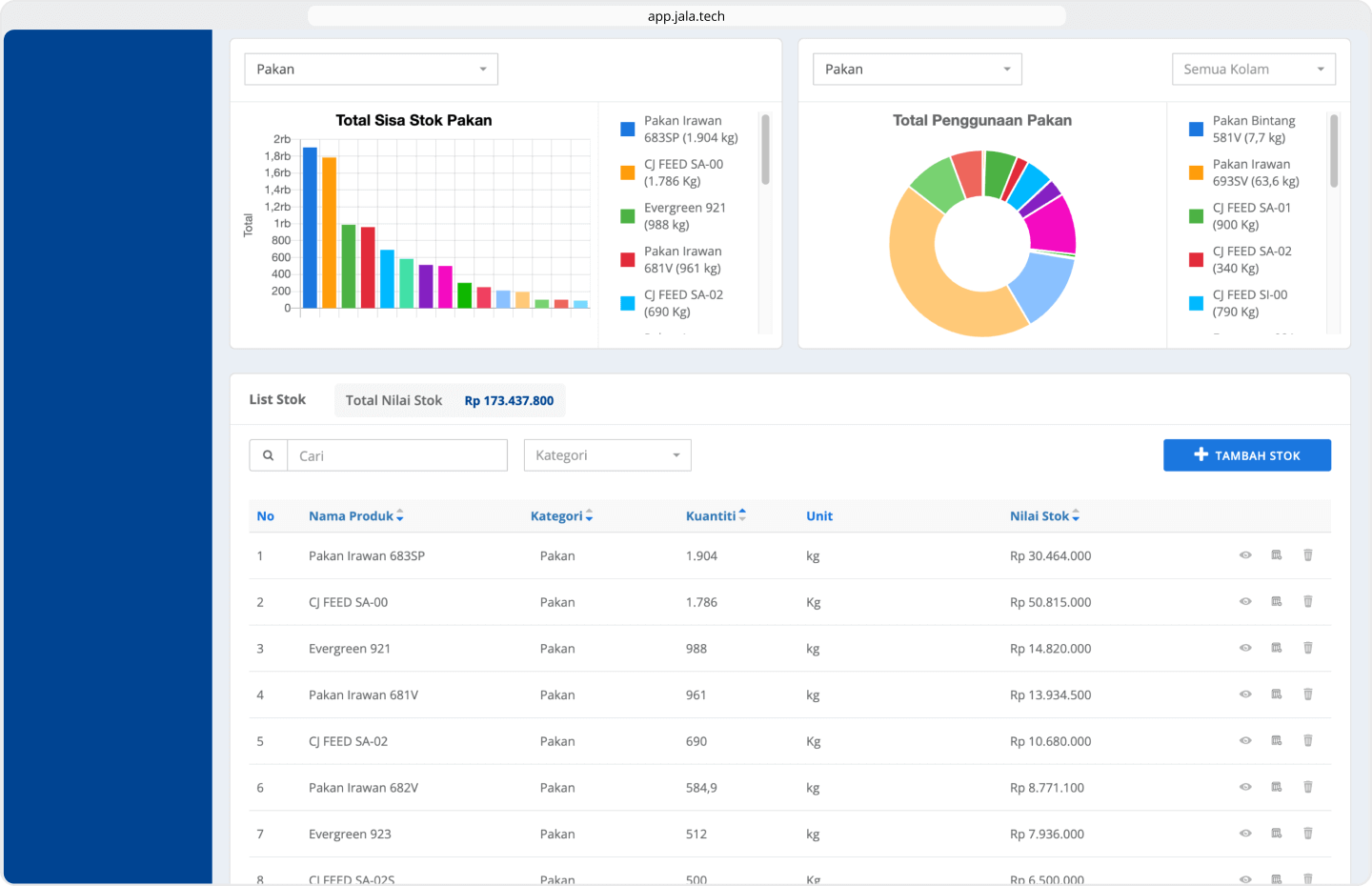

Using JALA’s software, farmers can input and record data from their ponds, from feeding schedules and water quality to shrimp mortality rate, harvest results and operating expenses. JALA’s algorithm processes the data into actionable insights such as recommendations to control the pond’s pH level or to adjust the feeding schedule. Farmers can also get forecasts on the harvest biomass as well as business-related forecasts such as potential revenue and profits.

With the user data JALA develops a generalized, big picture of Indonesia’s shrimp farming industry with data such as average shrimp survival rate, feed conversion ratio and harvest times available for JALA users. “We also have tools to monitor and analyze shrimp prices, including how they potentially correlate with other events,” Maduningtyas said.

Manufacturing snags

Prior to 2020, Jala had secured agreements to manufacture parts for its sensors in factories in China and the UK and had conducted pilot projects in Malaysia, Thailand, and Vietnam to prepare for regional expansion. Covid-19, however, put roadblocks in JALA’s path.

“We've suspended our overseas expansion plans to focus on the Indonesian market. The situation right now does not really allow for overseas expansion," Maduningtyas said. JALA had prepared to upgrade its software and app to respond to feedback it had received during the overseas pilot tests, such as language issues, but plans to test these improvements were shelved along with the overseas expansion activities.

“In countries like Thailand and Vietnam, we found that the English instructions were not easy to understand,” Maduningtyas said, adding that the different alphabet used in Thai also contributed to the language barrier.

JALA’s hardware manufacturing operations also hit a snag, as factories suspended operations multiple times throughout the year in response to Covid-19. Although the core technology of its new sensor device called Baruno is made and assembled locally, JALA also sources many important components from overseas.

Maduningtyas said that JALA was supposed to receive a “crucial component” from one of its vendors by the end of January 2021. However, due to a factory shutdown caused by a Covid-19 outbreak, the components arrived in Indonesia only at the end of February and reached JALA in March after customs processing.

“We're still doing our best for the hardware side, because it's an important tool for the data input,” Maduningtyas said. “So what we do is improve our service quality in both technical and customer support. We hope that in 2021 the manufacturing situation will improve.”

Predicting diseases early

With Covid-related delays in hardware manufacturing and imports, the JALA team refocused it efforts on software and customer service and achieved an average accuracy of more than 88% in its predictive analysis engines. The team is now working to achieve more than 95% accuracy. “Part of the reason for the lower accuracy is the quality of data input from the farmers," Maduningtyas said.

The company has opened a lab in Banyuwangi in East Java, where farmers can submit samples of their shrimp to detect diseases in the pond. Early detection, Maduningtyas said, can help farmers monitor the progress of the disease and take appropriate actions.

“If the disease is found early, we can observe the mortality rate. If the rates are not too high, the farmer can use various disease treatment techniques. But if the mortality rate continues to increase, the farmer can do an early harvest to get a smaller profit, which is more than what they would get if they waited it out until too many shrimps died.”

JALA’s work has not gone unrecognized. In early 2021, Forbes Indonesia picked Maduningtyas as one of its “30 Under 30” figures, along with other founders in Indonesia’s startup scene. Maduningtyas said she is glad to be featured and also acknowledged the founders of fishery marketplace startup Aruna, who were featured on the same list last year.

“[The Forbes award for Jala and Aruna] is an acknowledgement that Indonesia's aquaculture industry is developing into a more attractive proposition,” she said. “This is a proud moment for Indonesia's fishery and aquaculture industries.”